Most people are familiar with lee slope windloading, where winds blow over the top of a ridge or mountain, often accompanied by ridge-top cornices (overhanging drifts).

Here, there’s a different kind of windloading.

Crossloading occurs when wind blows across a slope and you need to look for different clues in different places than on lee-loaded slopes.

Unstable, crossloaded wind slabs are often found in low points, behind stands of trees that act as a wind fence and behind ribs or high points.

The most common crossloaded features, however, are gullies that run down the fall line, and there are couple of classic examples here.

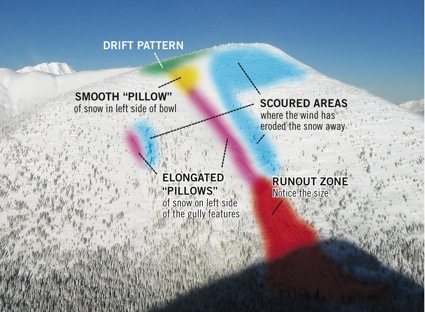

In this photo the drift pattern at ridge-top (green) and the very obvious “tails” of drifted snow on the right side of pretty much every tree, are a dead giveaway that winds have been blowing across the slope from left to right.

Check out the smooth “pillow” of snow on the left side of the upper bowl (yellow) and the fat, smooth, elongated pillows on the left side of the gully features (pink).

The snow here will be very deep, often hard, and usually very layered as each wind event over the winter creates a new layer.

Deeply buried, unstable layers are common here. Beside each loaded area on the right is a scoured area where wind has eroded snow away (blue), you can tell because the terrain looks rougher and trees and rocks are exposed.

The catch

In the deep pillows you risk triggering a thick, hard wind slab.

In shallow areas, you risk initiating a failure from a spot where the snow is weak and that failure travels into the deep snow pack above or around you and the whole mess comes crashing down on top of you when you least expect it (a remote triggered slide).

The gully creates a terrain trap where even a small avalanche piles up deep.

And even a relatively small feature like the central gully in this photo can produce big avalanches—notice the size of the run-out zone at the bottom of the gully (red).

That’s a lot of not-so-good factors.

I might tackle crossloaded features like this if danger is rated low and has been low for an extended period of time—and it’s spring, and there’s thick, hard, frozen crust that supports a sled; and you will not get stuck or spin your track through the crust; and there’s only one person on the slope; and there’s no one below me in the run-out; and… well, you get the picture. It’s a rare day when you’ll find me playing in the muzzle (run-out zone), the barrel (gully), or the chamber (upper slopes) of this loaded gun.

There’s lots of other terrain here that might be reasonable but the highly variable snow pack of a crosswinded slope like this makes advanced training, lots of avalanche experience and good local knowledge essential in assessing where or when it might be safe to ride the slopes through the small trees on either side of the crossloaded gullies.

The routes that look like they might be reasonable most of the time are the low angle ridges that form the left and right skylines.

Use them to get to the top for a great view, then go back the same way en route to friendlier terrain.

Sometimes you just have to say no to certain pieces of terrain if you want to maintain a reasonable margin of safety.