In an effort to solidify the unsteady terrain regarding avalanches, Avalanche Canada has upped its game and created a new flexible forecast system. So what’s new? Grant Helgeson, product manager and senior forecaster at Avalanche Canada, digs into the nitty-gritty.

Why did Avalanche Canada create a new flexible forecast system?

Previously the areas that we provide forecasts for were divided into 16 large, static regions in British Columbia, Alberta, Yukon, and Newfoundland. With these old regions, we would often see significant variation in the snowpack and weather pattern within one region. It was challenging for our team to develop forecasts for a region that had big differences within its boundaries. Users would have to carefully parse information to gain an understanding of conditions in their specific area of interest.

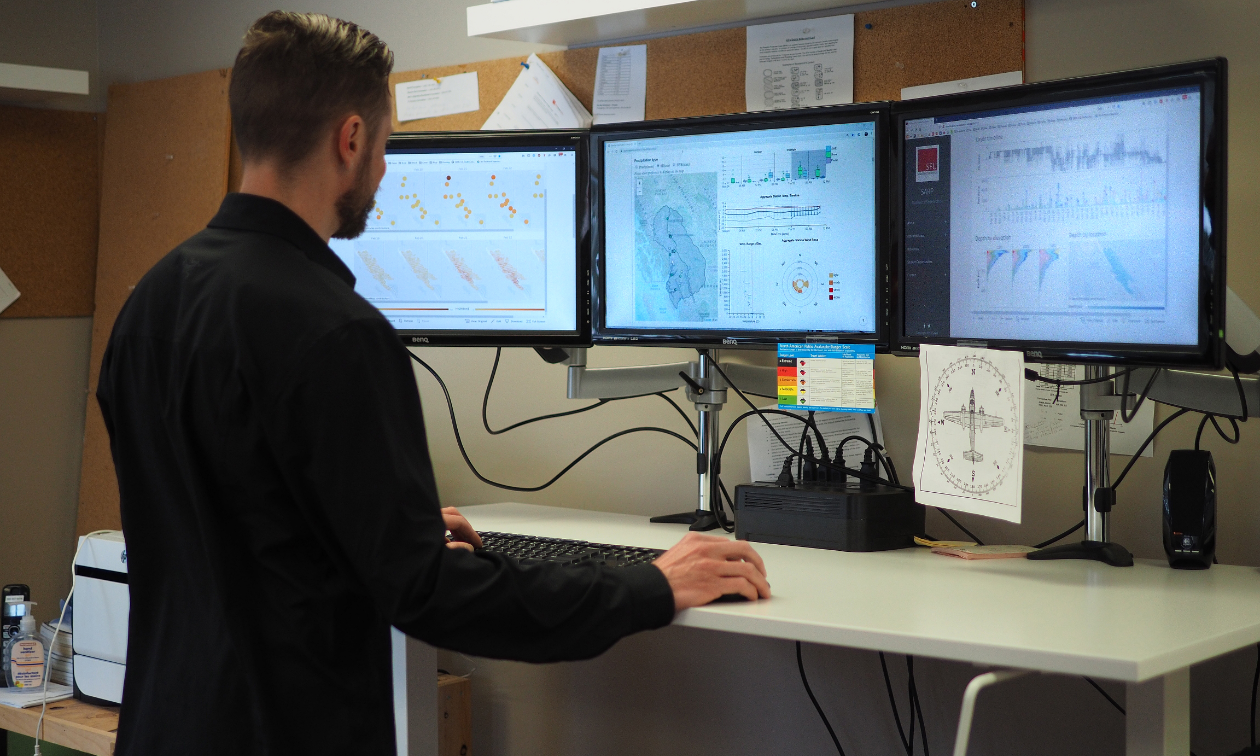

All the forecasts are written from our office in Revelstoke, B.C. Each on-duty forecaster looks at about 10,000 data points a day to produce the forecasts. There is usually quite a bit of individual analysis and group discussion as we tackle the challenges of the forecasting cycle and get the products out to the public.

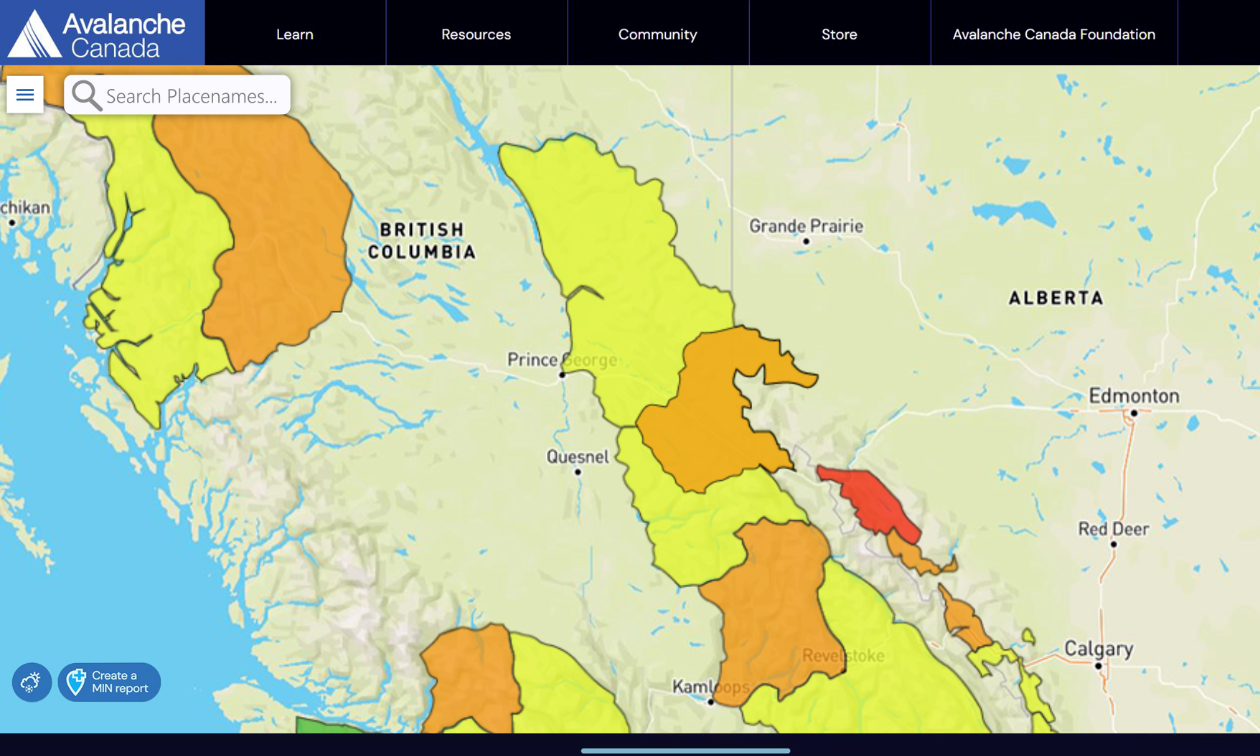

Our old static regions have been replaced with flexible regions based on conditions. This makes it much easier for our team to effectively communicate variability.

How has this new flexible forecast system been a game changer for you?

This new system enables us to provide more accurate forecasts when weather cycles impact some areas but not others, which leads to different snowpacks. A classic example of this is the old South Coast Inland forecast region, which included the Duffey Lake road in the north, and the Coquihalla Summit in the south. These two recreation zones often have very different snowpacks, and it’s great that we can now separate them when we need to.

How do you decide the regional boundaries every day?

Creating avalanche forecasts relies on a good understanding of the regional snowpack and the incoming weather patterns. We gain knowledge about the snowpack using a variety of tools and data sources. The forecasters then develop the forecast based on the current conditions and the incoming weather.

Last summer, our senior forecast team examined the areas we forecast for and created smaller subregions that allow us to better reflect conditions. To determine the subregions, we considered criteria such as snow climate, weather patterns, use patterns, and access routes. Analyzing this data resulted in 92 subregions. You won't see these on the map, but these subregions are the foundation of our new flexible forecast system. Using our forecasting software, subregions with similar conditions are grouped together to form a daily forecast region. This is our first season working with the 92 subregions, and the subregions are expected to evolve over time.

What features are riders finding most useful?

We’ve heard from riders that they appreciate the new search functionality. It’s super easy to find your riding area on the map and open the corresponding avalanche forecast.

We also updated the look and feel of the Avalanche Canada homepage map. The regions are now coloured to reflect their highest danger rating.

Sometimes adjacent regions will have the same colour but have a border between them. This indicates the highest danger rating is the same for both regions, but the information in the avalanche forecasts is different, which often comes down to the most important avalanche problems. These design changes reflect best practices in risk communication and are consistent with the approach used by most public forecasting agencies worldwide.

What visual aspects of the new flexible forecast system do you find most helpful?

We added a colour-blind safe mode to improve accessibility. You can click on the menu icon in the top left-hand corner to add and remove map layers and the hover-over danger rating icon.

How should snowmobilers prepare themselves before heading into the backcountry this winter?

Be sure to practice companion rescue. Avalanche Canada Training includes courses specifically designed for sledders. You never want to use this skill, but you should have it totally dialed. When we set up a practice site, we try to work in snow that is realistic, with a scuffed-up area tracked by sleds or a disturbed area like an old debris pile. Ideally, we practice on a slope, not just flat ground, and an area preferably over 100 metres long and 100 metres wide.

We start simple by burying one transceiver deep enough that we must work to find it. If the transceiver is buried 10 centimetres under the surface in a glove, that’s too easy. Instead, we bury the transceiver in a bigger target, like a big duffle.

We split our time between searching as a solo rescuer and as a team with a leader. We learn by practising with the same people we ride with, which allows us to work cohesively and have some muscle memory if we find ourselves involved with a real avalanche. It’s important to switch up the scenarios and have everyone you ride with take on different roles when you practice. As the season goes on, and we get more familiar with the simple scenarios, we introduce more complexity to our practice sessions, such as multiple burials, deeper burials, and close burials.

Most of all, we make it fun. If you are the competitive type, time yourself and your friends and make it a race against the clock. Keep it light and practice often. Bury a beverage or a favourite chocolate bar along with the transceiver as a reward for digging up the target. Most importantly, make sure your partners practice with you—your life depends on them.

Is there anything else you’d like to mention?

One last thing I want to highlight is how valuable the Mountain Information Network or ‘MIN’ is. If you’re out in the snow, please let us know what you see out there! You don’t need to be an expert, even a simple photo of you sledding, or an avalanche you observed is incredibly helpful to our forecasting team. The geographic extent of the mountains of western Canada is massive, and the more MIN posts we have, the better the avalanche forecast can be.