Karl Klassen is the public avalanche assessment bulletin manager for the Canadian Avalanche Association.

While he appreciates the beauty of this location, he also sees it as a complex snow-safety situation.

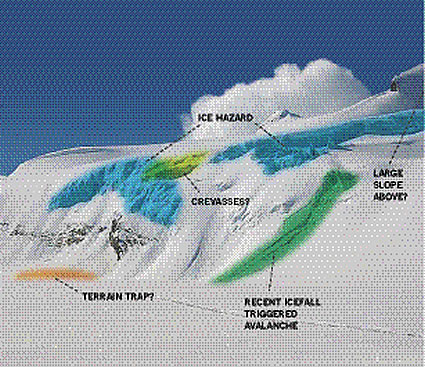

“Think ‘glacier’ and ‘terrain traps,’ ” said Klassen. “Glaciers add a whole other realm of complexity both in their own right—due to crevasses and icefall—and in combination with avalanches, crevasses are the worst kind of terrain trap.”

Hazards beneath the snow

“Crevasses are often well hidden under the snow and they’re common on flat terrain above an icefall,” said Klassen. “Falling into a crevasse is a death sentence unless your partner has technical rope rescue gear and skills. If pushed into a crevasse’s deep, narrow fissure, even a small avalanche can pile several metres of snow on you and your sled. Rescue is extremely difficult: it’s hard to get down there safely and the restricted space makes it hard to dig.”

Ice chunks—the size of a car

The ice outcroppings in two locations are also significant for their potential danger.

“Icefall is unpredictable and can occur at any time without warning,” said Klassen. “There’s some large chunks up there and one of them has recently fallen off, so clearly the ice is unstable and presents a direct hazard. Imagine a block the size of a car rolling over you—no avalanche required to do serious damage. Icefalls often trigger avalanches—ice is heavy and even a small chunk can trigger an unstable layer deep in the snowpack that would be difficult or impossible for you and your sled to set off.”

Don’t stop here

Klassen noted some serious hazards that were not easy for me to see:

“Below the rocky cliffs it looks like you go down into a gully feature or perhaps a flat area—another terrain trap where an avalanche from above will pile up deep.”

Look above you

Klassen also spoke of a hazardous feature that does not appear in the photograph.

“Above the flat area in the foreground with the lone track I suspect there’s a decent sized, steep peak with a steep face,” Klassen said. “(It’s) probably north facing given there’s a glacier below. I’m always concerned when there’s big terrain above me, especially north facing, alpine slopes where there’s lots of wind action and probably thin spots in the snowpack.”

An expert’s recommendations

By Karl Klassen, public avalanche assessment bulletin manager for the Canadian Avalanche Association.

I can see the attraction of this place. It’s beautiful and I’m drawn to it. Here’s how I’d handle it.

Go to www.avalanche.ca and read the bulletins for the area and/or get local information from a credible source (someone with avalanche training and experience—ideally a professional).

Don’t stop and regroup where there’s hazard above. Move quickly and spread out below any large slopes above, below those icefalls, and below the steep, rocky cliff areas to the left.

Don’t go up onto the glacier, without advanced training in how to travel safely on glaciers and how to use ropes to rescue someone from a crevasse.

The flats where the track is and perhaps going farther left if it’s not a major terrain trap are good places to do a sightseeing tour if:

- There are no persistent weak layers in the area.

- The danger is rated low.

- There’s been no recent heavy snowfalls or wind.

- It’s a cool, calm day.

Build avalanche assessment skills

Skills like Klassen’s can be attained through avalanche training. The Canadian Avalanche Association will be offering snowmobiler-specific courses this winter. Visit www.avalanche.ca/sled for bulletins in your sledding area, as well as times and locations of avalanche courses.