Her day starts out simple enough: get up, go to the office, browse the web, load up the truck and head out for a drive. From there, it gets exceptional: look for avalanches via snowmobile or skis, report snowstorms and—don’t forget to bring the dog—possibly locate and save someone from disaster.

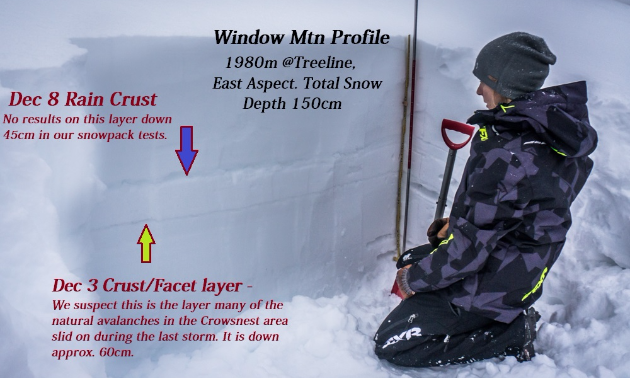

Jennifer Coulter is Avalanche Canada’s lead avalanche field technician for the South Rockies field team in Fernie, B.C., and surveys the Flathead, Sparwood, Elkford and even the Crowsnest Pass in Alberta. Once in the backcountry, Coulter records field weather observations such as a new snow, snowstorms, wind direction and temperatures. “We look for signs of recent avalanches and track critical layers in the snowpack that we think will be important in avalanche formation,” she said. “Sometimes on the way to and from these objectives we get a bit of sledding or skiing in too!”

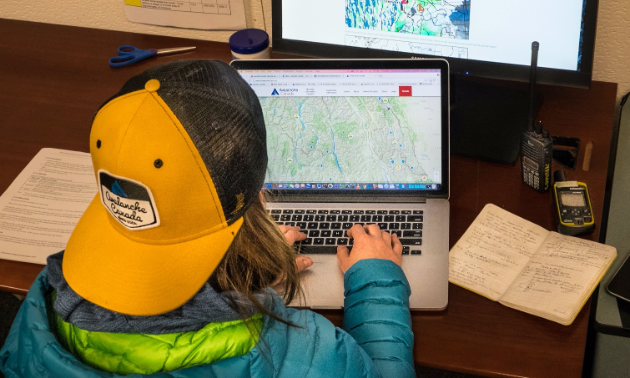

Coulter gathers information from and contributes to Avalanche Canada’s Mountain Weather Forecast for weather updates as well as the Mountain Information Network for avalanche conditions local riders have been experiencing in the area. The weather, snowpack and avalanche occurrence data Coulter collects end up reflected in the Public Avalanche Bulletin for the South Rockies and the Lizard Range/Flathead forecast regions.

“People need to check the avalanche forecast at Avalanche.ca,” said Coulter. “Armed with this information, you can make better decisions about what kind of terrain you should be riding in on any given day.”

When Coulter joined the Fernie Ski Patrol, she understood that avalanche terrain safety and avalanche mitigation were parts of the job description. “I wanted to get out into the backcountry, beyond the ski hill boundary,” Coulter said. “Living in a place like Fernie, I realized the destructive potential of avalanches and knew I needed to commit to my personal avalanche education to learn how to make decisions in avalanche terrain so I could have some fun and come home safe every night.”

Pika to the rescue

Coulter isn’t alone when patrolling the backcountry—she is assisted by her dog, Pika, a Belgian Malinois. Pika is a working dog that is certified in avalanche and wilderness search profiles. Together, Coulter and Pika are members of Fernie Search and Rescue, the Canadian Avalanche Rescue Dog Association (CARDA) and the British Columbia Search Dog Association (BCSDA), and the duo also works part time with the Fernie Alpine Resort Ski Patrol. If and when there is an avalanche in the backcountry, they get tasked by search and rescue (SAR) or the RCMP to respond. “She (Pika) is with me most places I go or at least kennelled in my truck nearby so that if I get a SAR callout, we will be ready to respond in a timely fashion as every second counts,” Coulter said.

As someone who heads into hazardous territory on a regular basis, Coulter is an expert on how to equip oneself for maximum survivability. “You’ve got to get the gear,” she said. “You and all your friends need to have a three-antenna digital avalanche transceiver, a shovel and a probe every time you go out. An avalanche airbag is a good idea too but doesn’t replace the need for any of the aforementioned gear.

“After that, you have to get some training. All that gear is worth nothing if you don’t practice using it. An avalanche rescue is scary and stressful. You don’t want that to be the first time you put your gear together. There are amazing Avalanche Skills Training (AST) courses and Companion Rescue Skills (CRS) courses taught by sledders, for sledders. These are a must for people riding in the mountains. Go ahead and challenge everyone in your group to take these courses. They could literally save your life.”

Thoughts to live by

Even with extensive preparation, planning and equipment, avalanches can still get the best of any snowmobiler. “A mentor of mine once said, ‘If you are going to be in an avalanche, better make it a very small one,’ ” Coulter said. “So far, I have stuck to that advice. When the avalanche danger is elevated or I have uncertainty about the avalanche conditions, I try not to expose myself to terrain that is capable of producing large, destructive avalanches. Another common saying in the industry is ‘the avalanche doesn’t know or care if you are an expert.’ ”

One way to mitigate risks is by assembling the right posse of riding companions. “I stick to riding with friends that have invested in their avalanche education and have similar goals and risk tolerances,” said Coulter. “Having a good group you trust is essential with backcountry riding. Everyone needs to be able to communicate well and be on the same page. ‘Every man for himself’ is a recipe for disaster in the mountains.”

Skis and snowmobiles

Coulter didn’t have an engine powering her skis when she began her avalanche adventure; she got her start at Fernie Alpine Resort as a professional ski patroller and avalanche dog handler. A couple of the key differences Coulter has noticed between skiers and snowmobilers is how they use terrain and communicate with one another.

“When I am travelling uphill from the parking lot to my goal in the alpine as a skier, I am doing so at a slower pace,” she said. “It is easier for me to notice the changes in the snow, weather and terrain at that speed, and to have conversations about what I am seeing with other members of my party. This continual information gathering helps me to make informed decisions and change my objectives according to the conditions.

“As a snowmobiler, I move much more quickly through the terrain—when I am not stuck (laughs). I can also expose myself to much more avalanche terrain in a day and get farther away from help than I usually do skiing. It takes extra effort for me to notice subtle differences in conditions, and sometimes it is easier to miss even obvious clues like signs of recent avalanche activity and wumpfing and cracking if I am not making a concerted effort to look for it.”

To combat the extra challenges in communicating with a group of snowmobilers as opposed to skiers, Coulter insists on a “helmets off, engines off” conversation at decision points and when entering avalanche terrain to make sure everyone is on the same page about how they are going to approach the terrain, go/no-go decisions and what the plan will be if things go wrong.

Coulter said sledding and skiing have one main similarity that all terrain users should adhere to. “Only expose one person to the slope at a time and stay out of runout zones,” she said. “This way, if something goes wrong, you will have one person in trouble and several rescuers instead of the other way around.”

Coulter loves what she does, not just because she gets to play outside with her dog in the snow, but because she is making a difference in people’s lives. “What I find most rewarding is building bridges between communities and working on finding new and interesting ways to effectively communicate avalanche risk to various user groups,” she said. “As a longtime SAR volunteer that has attended avalanche fatalities, anything I can do to make a difference in public avalanche safety is really rewarding to me.”

You can keep up with Avalanche Canada’s South Rockies Field Team on Facebook and Instagram.