Public avalanche bulletins are a key—one could argue THE KEY—tool in your toolbox. Think about it. I’m pretty sure your goals and our goals are the same: we want to have the most wicked day of riding possible, and return home unscathed and ready to do it all over again the next day.

If your goal is a long life of backcountry fun, we encourage you to consider risk management in this way: focus on avoidance and prevention. Understanding what the problems are and where they may be hiding help us choose where to ride.

Professional avalanche forecasters compile past and forecasted mountain weather reports with hundreds of data observations gathered by experienced backcountry guides and personnel from commercial operations throughout our actively used mountain areas. In order to create a concise report, descriptive icons, specialized vocabulary and phrases are used to communicate to the recreational public. While the reader might understand the individual words used in these reports, without at least taking an Avalanche Skills Training (AST) Level 1 course, it is doubtful whether the reader will get the full picture.

Below are three of the top five common misconceptions that arise when reading public avalanche bulletins:

1. Travel habits when the danger rating is Considerable

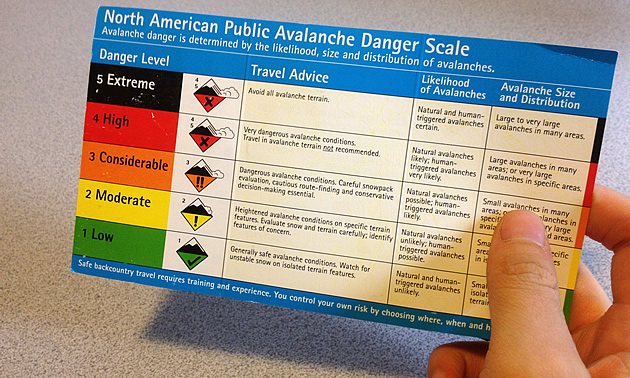

Considerable is a more serious rating than most people give it credit for. It is not in the middle, or average or just orange. On the North American Public Danger Scale, the definition for Considerable reads “Dangerous avalanche conditions. Careful snowpack evaluation, cautious route-finding and conservative decision-making essential.” What is just as necessary is to understand exactly where this rating applies. For example, is it for the entire mountain range or just the northeast aspect of the treeline?

Slopes not matching those highlighted in the current bulletin will likely have a danger rating of Moderate or Low—much safer options.

2. Wind slab problems versus persistent weak layers

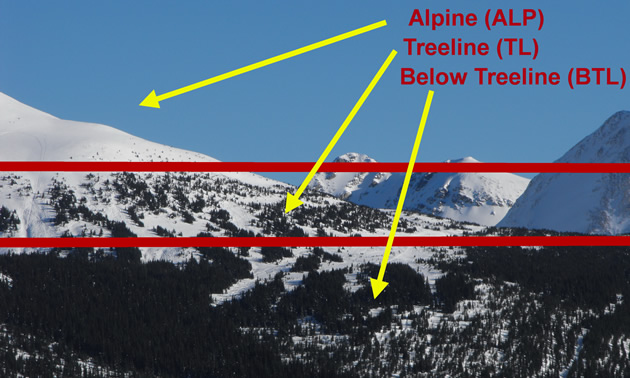

A rating of Considerable with wind slabs is a much easier situation to manage than a riding day with Considerable and a persistent surface hoar layer. Unstable wind slabs tend to be confined to alpine (ALP) and treeline (TL) ridgelines and steep features. The easiest choice in this situation is to drop down in elevation where the slopes aren’t wind affected.

Surface hoar, however, can create problems on all elevations and all aspects (sides of the mountain). It may be hard to find slopes without a buried surface hoar problem. On days like these, having fun is more about lower angle riding.

3. Alpine, treeline and below treeline (BTL)

Most people overestimate their exposure to avalanches as they think they always ride in ALP or TL. People tend to believe that BTL only refers to the valley bottom. This is not so.

Treeline is the narrow elevation band where the conditions are allowing sparse trees to grow. Meadows, burns, cutblocks and trails are all in the BTL elevation. Oftentimes, this elevation band has more stable snow and therefore offers more options to have fun and stay safe.

Information from avalanche bulletins helps us to gain understanding so we can make better decisions and remain incident free, resulting in a long life and having the most fun.

Try this! On your next trip to the mountains, conduct an informal survey and ask the riders questions about the avalanche conditions. What personal observations did they make along their route? Did they read the Canadian Avalanche Centre avalanche bulletin? More importantly, did they understand it?

No matter the conditions, the answer is always smart selection of terrain. How do you choose? Avalanche skills training can teach you what to look for. For information on AST Level 1 courses, visit Zac’s Tracs.